The Khanate

Bukhara did not re-emerge from Samarkand's shadow until

Abdullah Khan, descended from Genghis Khan's grandson Sheiban, rebuilt

most of it in the second half of the 16th century. He also formed the Sheibanid

empire by conquering Baikh, Fergana, Tashkent, Khorasan and Khorezm.

During

the 17th century the empire shrank back to its core between the Amu Daiya

and Syr Darya rivers and became known as the Khanate of Bukhara. Abdullah

Khan's less competent Sheibanid successors wasted their limited energies

bickering with other khanates until Nadir Shah invaded from Persia and

founded the Astrakhanid dynasty in 1740. In 1784 the merely unimaginative

Astrakhanids were replaced by the positively

backward-looking Manghits, who called themselves emirs instead of khans

and ruled till 1920. Their founder, Emir Maasum, was, according to Curzon,

'a bigoted devotee, wearing the dress and imitating the life of a dervish'.

He was also, by contemporary standards at any rate, a pervert. If the writings

of a German doctor who penetrated Bukhara in disguise in 1820 are to be

believed, the emir retained, in addition to his harem, 'forty or fifty

degraded beings', with whom he indulged in 'all the horrors and abominations

of Sodom and Gomorrah'.

During

the 17th century the empire shrank back to its core between the Amu Daiya

and Syr Darya rivers and became known as the Khanate of Bukhara. Abdullah

Khan's less competent Sheibanid successors wasted their limited energies

bickering with other khanates until Nadir Shah invaded from Persia and

founded the Astrakhanid dynasty in 1740. In 1784 the merely unimaginative

Astrakhanids were replaced by the positively

backward-looking Manghits, who called themselves emirs instead of khans

and ruled till 1920. Their founder, Emir Maasum, was, according to Curzon,

'a bigoted devotee, wearing the dress and imitating the life of a dervish'.

He was also, by contemporary standards at any rate, a pervert. If the writings

of a German doctor who penetrated Bukhara in disguise in 1820 are to be

believed, the emir retained, in addition to his harem, 'forty or fifty

degraded beings', with whom he indulged in 'all the horrors and abominations

of Sodom and Gomorrah'.

Maasum's son Nasrullah received in 1832 the audacious,

polyglot British officer Alexander Burnes, whose Travels Into Bukhara contains

the most colourful and intelligent description available of the city in

the early 19th century. Its population of 150,000 was half that of pre-Mongol

times, and three quarters of it was of slave extraction, mostly descended

from Persian slaves captured and sold at Bukhara's infamous slave market

by Turkmen nomads. There were also Russian slaves:

'A red beard, grey eyes, and fair skin, will now and then

arrest the notice of a stranger, and his attention will have been fixed

on a poor Russian, who has lost his country and his liberty, and drags

out a miserable life of slavery.'

Not everyone was oppressed. Hindus, Jews and European

merchants lived and traded unmolested in return for observing certain ground

rules. Only Muslims might ride horses within the city. Whosoever failed

to look away as the emir's harem passed risked 'a blow on the head'. Anyone

out at night without a lamp would be assumed by the emir's police to be

a burglar. And the sabbath (Friday) was strict: 'If a person is caught

flying pigeons on a Friday he is sent forth with the dead bird round his

neck, seated on a camel.'

Students were numerous-Burnes reported 366 madrasas each

with from 10 to 80 students-and privileged; each had a right to a yearly

maintenance grant from their madrasa, and to a share of the state's income.

They were not all young: Burnes found 'many of them grave and demure old

men, with more hypocrisy, but by no means less vice, than the youths in

other quarters of the world.'

Women blackened their teeth and were absolutely not to

be looked at except by their husbands, who were entitled to shoot peeping

Toms.

The city centre, finally, contained 'many ponderous and

massy buildings, colleges, mosques and lofty minarets,' while 'the common

houses are built of sun-dried bricks on a framework of wood, and are all

flat-roofed'-as they are today.

Age did not mellow Nasrullah. Ten years after Burnes'

visit he gained worldwide notoriety by throwing two less diplomatic British

officers, Colonel Stoddart and Captain Conolly, into his bug pit and then

beheading them, slighted that Queen Victoria had not pleaded in person

for their lives. It was one of the most gruesome and, thanks to an eccentric

clergyman, highly publicized episodes in the Central Asian war of nerves

between Britain and Russia which Kipling called the Great Game (see Zindan).

Bukhara had huge symbolic importance for Central Asian

Muslims and for British Russo-phobes who thought its annexation by St Petersburg

would be a prelude to a Russian invasion of India. So Russia trod carefully.

When Bukhara's clergy declared a holy war against her in 1868, General

Kaufmann had his pretext for attacking Samarkand to protect Tashkent. He

didn't meddle with Bukhara but he did take control of her water supply.

The holy war petered out, the frustrated clergy led a revolt against the

emir, and the Russians stepped in to crush it for him. Without ever attacking

the city they reduced it to vassal status in a treaty of 1873.

Colonial Bukhara

' Russian, or 'New' Bukhara was even more separate from

the old city than were the Russian cantonments at Tashkent and Samarkand.

Born when the railway came from Krasnovodsk in 1888, it was centered on

the station ten miles south of Bukhara proper at Kagan. The now disused

Russian church is still there.

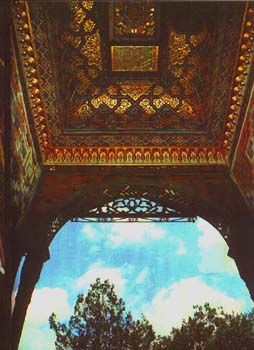

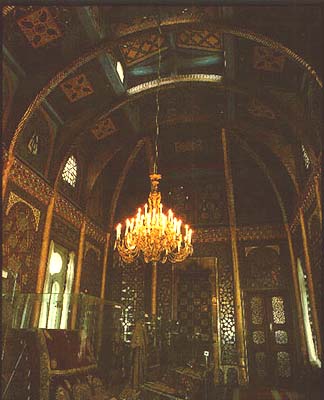

There

followed a delicate 30-year-long, four-cornered power struggle. In the

Ark and the gaudy summer palace resided the last emir, Alim Khan, hanging

onto the trappings of 'power. Outside the city strutted the Russian garrison

and political agent, wanting stability and trade and prepared to support

the emir as long as he delivered it. In the mosques and madrasas the mullahs

swore death to the infidel and cursed the emir for his dubious loyalty.

On street corners and in smoke-filled rooms angry young men whispered a

dangerous new jargon about reforms and rights and pan-Turkic brotherhood.

There

followed a delicate 30-year-long, four-cornered power struggle. In the

Ark and the gaudy summer palace resided the last emir, Alim Khan, hanging

onto the trappings of 'power. Outside the city strutted the Russian garrison

and political agent, wanting stability and trade and prepared to support

the emir as long as he delivered it. In the mosques and madrasas the mullahs

swore death to the infidel and cursed the emir for his dubious loyalty.

On street corners and in smoke-filled rooms angry young men whispered a

dangerous new jargon about reforms and rights and pan-Turkic brotherhood.

In 1910 a general massacre of Shi'ite Muslims by Sunnis

ended the city's traditional inter-denominational harmony and was blamed

on the reformers, who went underground. The Russian premier Stolypin threatened

outright annexation of Bukhara. To forestall it the emir promised

financial and educational reform but entrusted it to the clergy, who smoth-à

ered it. In the years leading up to the Russian Revolution of 1917 the

once-liberal underground, funded by a merchant millionaire called Mirza

Muhitdin Mansur-oghli, grew more frustrated and extreme. But it was not

the works of Marx and Lenin they were reading. Mansur-oghli paid for them

to go to university in Istanbul and get high on the anti-Russian, pan-Turkic

teachings of Mustapha Kemal.

The Russian Revolution

When revolutionaries took over St Petersburg and Moscow

in 1917, the Emir of Bukhara Was nearly dizzied by the political weathervane.

At first, goaded by a murky Russian agent with the un-Russian name of Miller,

who had himself switched quickly from the czarists to the communists, he

offered his own package of reforms. But when he saw that H Bukhara was

not at the top of revolutionary Moscow's agenda he withdrew it. His people

seethed. A communist among them, Khodja-oghli (Khojaev), told the Bolsheviks

in Tashkent that Bukhara's proletariat was ready to revolt. He was wrong.

When the Bolsheviks came the emir had them slaughtered at the station,

and Bukhara became unofficial centre of the Central Asian counter-revolution.

Early in 1920 the emir forbad trade with Russia or Soviet

Turkestan. It was a self-imposed blockade. By July three quarters of the

khanate's livestock was dead and its people were running out of water.

The Istanbul-trained Young Bukharans were at odds with the new and mainly

Russian Bukhara Communist Party-but a marriage of convenience looked imminent.

In August the Red Army bombarded the city and in September,

while the emir was away trying to assemble an army, it took possession.

Moscow still feared provoking an Islamic uprising, so home-grown revolutionaries

were allowed to found the Bukharan People's Republic, nominally independent

of the Soviet Union. But the BPR proved awkwardly receptive to overtures

from Istanbul, and when the Bolsheviks had a breathing space from their

European struggle, they purged Bukhara's communists. On 19 September 1924

the Bukhara Communist Party voted unanimously at its fifth congress to

abolish the BPR and found a Soviet Republic in its place.

Soviet Bukhara

As a stronghold of Muslim culture, Bukhara presented the

evangelically atheistic Bolsheviks with a tricky choice: to raze it and

start again, or to let it decay. They chose the latter. In the 20 years

following the revolution its population fell by half. Fitzroy Maclean wrote

after his visit in 1938: 'With the exception of a highly incongruous Pedagogic

Institute which has made a somewhat half-hearted appearance within its

walls, the dying city of Bukhara has remained purely Eastern. The only

changes are those which have been wrought by neglect, decay and demolition.'

The purging of anti-Soviet elements had continued steadily,

culminating in 1938 with the execution after a show trial of Bukhara's

most famous communist son, the same Khojaev who had invited the Bolsheviks

to lead an insurrection in 1918 and who subsequently became Soviet Uzbekistan's

first president.

The Soviets did Bukhara the favour of draining and filling

in most of its famous pools (there had been 100 when Burnes paid his visit).

The diseases they harboured-'Bukhara Boil', 'Sartian Sickness', Guinea

worm-disappeared, but so did most of the city's soul. An alternative water

supply arrived in 1968 in the form of the 180-km Amu-Bukharski Canal from

the river Amu-Darya. Water was suddenly ten times more abundant and President

Sharaf Rashidov took the credit while the Aral Sea took the strain.

Mean while Bukhara was industrialized. Processing plants

were built on its outskirts for cotton, silk, wool, meat and milk. The

city was honoured with the Soviet Union's biggest Karakul 'factory', in

which Karakul lambs are killed before or shortly after birth for their

tightly-curled coats which are said to be warmer and softer even than those

of Astrakhan lambs. There is also a guano factory staffed by

pigeons.

[back]