Museum open 9 am-6 pm daily.

After so much death and religion it's a relief to get

clear of the city center and inhale some secularity on the hill from which

Ulug Bek studied the heavens. The remains of his observatory are 20 minutes'

walk north of the bazaar up the Tashkent road. Alternatively, take marshrutnoe

taxi 17 from the Hotel Samarkand or the bazaar.

The Conquest of the Stars

The grandson of Tamerlane, Ulug Bek was less interested

in conquering the earth than  the

stars. His was the best-equipped observatory in the medieval world; a magnet

for leading scientists and a center of progressive, often heretical thought.

'Where knowledge starts religion ends/ was the motto of his teacher, Kazi

Zade Rumi, and Ulug Bek's quest for enlightenment led him to sponsor debates

on such topics as the existence of God. This did not go down too well with

Muslim orthodoxy, and among those who found his beliefs hard to stomach

was his own son, who assassinated him on 29 October 1449. Shortly afterwards,

religious fanatics tore down the observatory.

the

stars. His was the best-equipped observatory in the medieval world; a magnet

for leading scientists and a center of progressive, often heretical thought.

'Where knowledge starts religion ends/ was the motto of his teacher, Kazi

Zade Rumi, and Ulug Bek's quest for enlightenment led him to sponsor debates

on such topics as the existence of God. This did not go down too well with

Muslim orthodoxy, and among those who found his beliefs hard to stomach

was his own son, who assassinated him on 29 October 1449. Shortly afterwards,

religious fanatics tore down the observatory.

Ulug

Bek's astronomical observations, which put him on a par with Copernicus

or Kepler, did not become known in the West until 1648, when a copy of

his Catalogue of Stars was discovered in Oxford's Bodleian Library. He

had plotted the position of the moon, the planets, the sun and 1018 other

stars with amazing precision, and calculated the length of the year to

within 58 seconds (or even less; the earth span slower then than it does

now). These were some of the greatest achievements of the 'non-optical'

(pre-telescope) era of astronomy.

Ulug

Bek's astronomical observations, which put him on a par with Copernicus

or Kepler, did not become known in the West until 1648, when a copy of

his Catalogue of Stars was discovered in Oxford's Bodleian Library. He

had plotted the position of the moon, the planets, the sun and 1018 other

stars with amazing precision, and calculated the length of the year to

within 58 seconds (or even less; the earth span slower then than it does

now). These were some of the greatest achievements of the 'non-optical'

(pre-telescope) era of astronomy.

Having fallen victim to one orthodoxy, Ulug Bek was a

ready-made hero for another. The Soviets made him the object of a minor

cult and officially designated his murder as 'tragic'.

What nobody knew was where, or quite how, Ulug Bek had

worked. Then in 1908, after years spent studying ancient manuscripts, a

Russian primary school teacher, amateur archaeologist and former army officer

called Vladimir Viatkin unearthed the lower portion of a giant sextant

on Kukhak Hill beside the road to Tashkent. It was one of the major finds

of the 20th century.

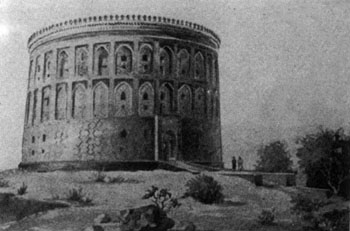

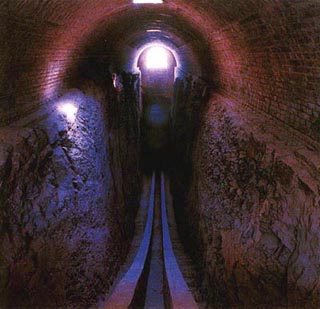

The original sextant was a perfect arc of marble-clad

brick, 63 metres long with a radius of 40 m, calibrated in degrees and

minutes, decorated with the signs of the zodiac and aligned with one of

the earth's meridians. Observations and measurements were made  with

an astrolabe mounted on metal rails either side of the sextant. What survives,

complete with calibrations and fragments of rail, is the lower section

of the arc, set in a deep rock trench to minimize disturbances from earth

tremors. The arc originally continued upwards above the trench inside a

round, three-storeyed observatory at least 30 m high. Traces of its foundations

are all that remain. The top two floors were arcades used as solar and

lunar calendars. Ulug Bek probably used the ground floor as a summer residence.

There is a small museum on Uzbek astronomy and the opening of Tamerlane's

tomb (see Gur Emir below). The astronomy section includes an old engraving

of great astronomers in which Ulug Bek sits alongside Copernicus and Galileo

dressed as a Cossack, whose garb was the most eastern-looking the engraver

could envisage. The modest grave near the entrance to the sextant is Viatkin's;

he was buried here in

with

an astrolabe mounted on metal rails either side of the sextant. What survives,

complete with calibrations and fragments of rail, is the lower section

of the arc, set in a deep rock trench to minimize disturbances from earth

tremors. The arc originally continued upwards above the trench inside a

round, three-storeyed observatory at least 30 m high. Traces of its foundations

are all that remain. The top two floors were arcades used as solar and

lunar calendars. Ulug Bek probably used the ground floor as a summer residence.

There is a small museum on Uzbek astronomy and the opening of Tamerlane's

tomb (see Gur Emir below). The astronomy section includes an old engraving

of great astronomers in which Ulug Bek sits alongside Copernicus and Galileo

dressed as a Cossack, whose garb was the most eastern-looking the engraver

could envisage. The modest grave near the entrance to the sextant is Viatkin's;

he was buried here in

accordance with his will.

[back]