With the arrival of the first Chinese in the mid 2nd

century Bñ, Samarkand entered an era of invasion-proof prosperity

and semi-mythic international status. It was to last more than a thousand

years and it began because the Chinese found that silk, which they alone

knew how to make, was worth more than its weight in gold in the empires

of the West.

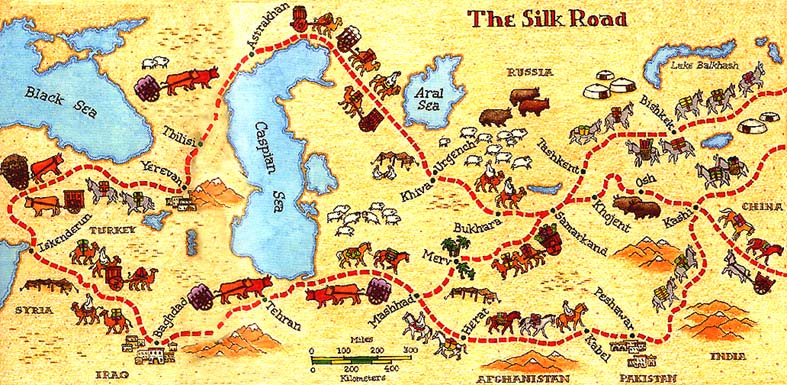

Samarkand was at the very center of the Silk Route system.

The only Chinese caravans which did not pass through it were those heading

straight for Russia from the passes of the Tien Shan-and Russia was but

a minor client until of Kiev rose to power and prosperity in the 9th century.

Considering the volume of through traffic, remarkably

little is known about life in ancient Samarkand. Archaeologists are hampered

by the wind; before Tamerlane the city was built mostly of mud, so that

over the centuries buildings simply dried up and blew away. And Asian caravans

do not seem to have kept diaries. So we have an account by Arrian, Alexander's

chronicler, and then nothing until 1200 years later when the Arabian traveler

Abulkasim ibn-Khakal was much taken by Samarkand's canals. Marco Polo's

Travels kept alive the legend of Samarkand for Europeans, even if he never

actually went there. Thereafter Europeans arrived at the rate of about

one every hundred years until the 1860s. In the end the rarity of writings

about Samarkand is eloquent confirmation of its extreme isolation; until

1868 it was still, in Geoffrey Moorhouse's words, 'a great deal more remote

from the rest of civilization than the moon is today.'

At least we know that when those first Chinese arrived,

Samarkand was part of the (Persian) Achaememd empire, and that, like the

rest of Transoxiana, it passed to Kushans, Hephthalites and Turks before

the coming of the Arabs. From bowls and fire-proof altars in Afrasiab's

museum it also seems that the potting wheel arrived on the scene in the

lst century ad and that the prevailing religion was Zoroastrianism, or

fire-worship.

The secrets of silk making reached the West in the 6th

century and the flow of Chinese silk through Samarkand gradually diminished

as Italy, Spain and southern France began making their own. But Samarkand

was to remain a crossroads of international trade in other commodities

until sea routes were established between Europe and the Orient in the

16th century.

[back]

|